Over the next two months, a bunch of guys (and one woman) at my workplace are competing against each other to see who can drop the largest percent of their total body weight (not actually fat, just weight, which includes muscle). There’s significant money involved. It’s serious. The winner will be the person who adheres to these practices most diligently.

The winner will eliminate all processed sugar from their diet.

Processed sugar not only causes significant water retention, it also majorly interferes with metabolic processes, hormonal signaling, increases triglyceride levels (and generally turns the blood lipid profile to sh*t), and fuels the growth of cancer cells. Like to feel hungry when your body doesn’t actually require energy? The loser will eat sugar. The loser will consume sugar while restricting calories, white-knuckling the ride on a busted Cyclone of a blood sugar roller coaster, watching their hopes of comfortably maintaining a consistent caloric deficit be snuffed out by the demon molecule. A couple of pieces of fruit each day is fine because the fructose is buffered by water, fiber, vitamins and minerals. The winner will remember this.

The winner will exclusively eat wet, organic foods in their most unrefined form.

No boxed or packaged foods. Vegetables. Eggs. Sweet potatoes. Sardines. Some fruits. A few servings per week of white potatoes and rice are ok too (blasphemy, maybe). What’s that thing about wet foods? That sounds nasty. I’ve written about it elsewhere on this blog, but the synopsis is that if your food isn’t hydrated, it will detract from your efforts. Most processed foods aren’t wet or nutrient rich, and as such, are metabolically disorienting. Take, for example one ounce of baked Lay’s chips is, which I think are quite unhealthy. On the other hand, six oz of organic russet potato is quite good. Same calories, completely different metabolic effects. Baked Lay’s: no water, negligible fiber, no minerals, sodium imbalance. Organic russet potato: fiber, water, minerals, naturally occurring sodium. After baked Lay’s you = hungrier. After white potato with butter you = fuller. Yes, I said butter. Read the next one.

The winner will not be afraid of eating fat. In fact, the winner will eat more fat as a percentage of their calories than the loser.

You might be ready to cast this article off after reading that one, but hang on a sec. It’s entirely possible to shed body fat simply by cutting carbs and increasing fat intake. I do it whenever I feel like dropping a couple of pounds. The idea that fat makes a person fat is corny and mad old. It’s an idea that remains legitimate only in the minds of crabs. Sugar is far better at making a person fat because of the metabolic havoc it wreaks. Dietary fat is the ultimate tool for fat loss, but it’s got to be the right type of fat: that is, mainly saturated. Saturated. You read that correctly. The villification of saturated fat based on the famous (and famously debunked) 1958 “diet-heart hypothesis” is clearly less chic these days, and there’s a reason for it: naturally occurring saturated fat is a nutritional beast. Not only does it not create an unfavorable blood lipid profile, but it also helps balance to the endocrine system. Sugar does exactly the opposite. Although increasing saturated fat intake can increase total cholesterol, total cholesterol has ABSOLUTELY zero to do with cardiovascular health and heart attack risk. HDL:LDL ratio is important, total cholesterol:HDL is more important, and LDL particle size is maybe the most important. The point is that replacing sugar and non-hydrated carbohydrates with the right type of saturated fat can dramatically improve all of these markers. So what’s the right type of saturated fat? First, a little on what’s not the right type of fat: vegetable oils i.e. polyunsaturated fats. They’re are generally terrible because they are so easily oxidized before and after consumption, which causes all sorts of cell-level damage to the cardiovascular system. Canola, corn, soybean, sunflower, safflower, peanut, cottonseed, grapeseed and sesame oils are positively demonic. Margarine and “butter-like spreads” are all simply solidified vegetable oils and possibly even worse for you than the oils themselves because of the chemical stabilizers used in them. Monounsaturated fats, like avocado oil and extra virgin olive oil are definitely better. Saturated fats, like unrefined virgin coconut oil, organic butter from exclusively pasture-raised cows, and humane raised eggs (humane means the chickens are bred in healthier, less contaminated conditions) are best. Small amounts (less than two oz) of extra dark chocolate (~85% or above) is also a winner (must be organic though, since conventionally raised cacao crops are can carry a load of pesticides). The proper type of saturated fat is second to none at helping to curb appetite and calibrate the body’s autoregulatory mechanisms, assisting in cellular repair (cell walls are ~50% saturated fat) and improving immune response, but it also helps balance hormone levels–especially testosterone in men. Why would this be important to the winner of the weight loss challenge? The fullness part is obvious. But when a person is reducing energy intake, i.e. going on a “diet”, it’s easy to lose focus, become depressed, lose their mind, and be generally miserable. All this crap can be counteracted to an extent by the positive hormonal effects of the right saturated fats. This isn’t to say go apesh*t on them, and it’s also important that if you’re eating animal fat that it comes from the cleanest animal meat (that means organic definitely and certified humane, when possible). Environmental toxins are readily stored in fat cells, so any crap eaten by the animal ends up in its fat cells, and will end up in you. But it is to say that shifting the balance of calories from processed carbohydrates to unrefined plant-based saturated fat can be a very smart thing to do.

The winner will track energy in and out.

I’m generally not a proponent of tracking calories, but energy balance is important when it comes to losing weight. There’s some nuance to this argument in that fat loss is the product of both caloric restriction and proper metabolic signaling, the efficiency of which is enhanced when whole, natural foods are consumed. But still, the law of thermodynamics is inflexible. Fewer calories in than out will result in weight loss. There are some great tools out there for tracking consumption, like MyFitnessPal, and for tracking activity (FitBit etc.).

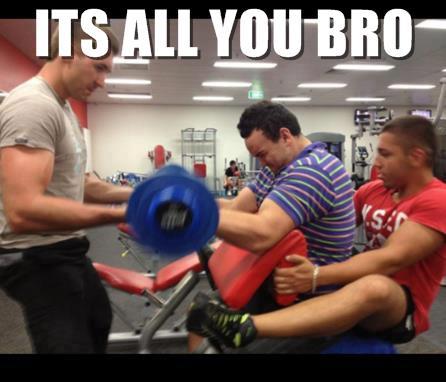

The winner will eliminate most structured cardio in favor of lifting heavy weights. Is your mind blown?

The most effective way to force the body to prioritize shedding fat when in a caloric deficit is by providing a reason for it to retain muscle fiber. In a caloric deficit–especially in the presence of structured and more intense cardiovascular exercise–the body wants to shed muscle along with fat because muscle is metabolically expensive to maintain. Create a reason for the body to prioritize muscle maintenance and fat loss will accelerate. And one note on lifting–we’re not talking about curls, sit-ups and shrugs here. We’re talking about barbell squats, deadlifts, overhead presses, Pendlay rows and the like. Nothing complicated, but big movements that tax most of the large muscle groups and elicit a hormonal response most conducive to fat loss. There’s a good deal of detailed content on this topic sprayed across this blog. If you’re in an energy deficit, you won’t put on muscle (so don’t worry about adding body weight).

If the person who wants to win is really serious, they will fast every day for a significant number of hours and do it for the rest of their life.

This is the big one. When properly applied, fasting is the most incontrovertibly efficient path to fat loss. This blog is replete with posts about the virtues of regular fasting, not the least of which is that it’s an awesome tool for weight loss and effortless weight management. Those last three words are huge. Most of us are pretty familiar with the weight-loss rebound phenomenon, characterized by big fat loss followed by big fat gain. The simple reality is that the practice that made the big fat loss possible was very likely unsustainable. Atkins, or extremely low-carb diets are examples of programs that are nearly impossible to sustain for a lifetime. Daily fasting is a metabolically and nutritionally sound lifestyle change. I’m living proof that it’s possible, and pretty damn easy to fast for 20 consecutive hours per day, every day. I’ve been doing it for more than three years and have only benefited from it. With specific application to fat loss, fasting, in my opinion, is the only way to go. When you’re fasted, your blood sugar levels are rock steady, and your metabolic system draws exactly whatever energy it requires from muscle glycogen, liver glycogen and fat stores. I call it a “clean burn”. Mental focus and cognition are noticeably increased due to the upregulation of a chemical termed brain-derived neurotrophic factor. When you’re following a traditional diet on which you’re eating several times per day but just a lot less food, your blood sugar levels swing around, making you feel hungrier and less likely to be able to comfortably control your eating. Ever feel sluggish after lunch? You can blame insulin for that. No insulin = no sluggishness. To be uncouthly honest, the “six small meals per day” thing is raging bullsh*t, an utter farce, and a nonsensical, pandering load of guar gum. The only reason why the TV “nutritionists” are pushing this hooey is because as soon as you eat, your blood sugar goes haywire. That’s the reality. Eating six times a day is essentially methadone after heroin, or like cocaine after cocaine.

Fasting only takes a day or two to get used to. Water, black coffee and unsweetened tea can be taken, but nothing else. No diet sodas. Nothing else. The beauty of fasting is that once you’re at your desired weight or body composition, counting calories is no longer necessary. They body’s tendency or “desire” to autoregulate is more palpably expressed when the eating window is compressed. Simply, it’s more difficult to overeat when there’s less time to do it. Don’t get this twisted though–if you eat cake and ice cream during the eating window, none of this matters. But if you eat unprocessed, simple foods during the eating window, you actually, exactly, literally will never have to think about managing your weight ever again because your body will do it for you. Even more spectacular is that fasting dramatically boosts autophagy, the process by which cells recycle metabolic and other waste, especially in the brain.

The winner will not pay any mind to mularkey about not eating before bed.

Because if you fast, your only realistic option is to eat before bed. If your energy balance and food selection are on point, it matters not in the least.